NoCo Science Education Blog: The Power of Learning Outdoors with Carol Seemueller

by Victoria Jordan

“We stopped doing field research at Cathy Fromme Prairie because the students had too many rattlesnake encounters,” Carol Seemueller explains. “We moved to other natural areas around the city.”

Carol Seemueller, recently retired biology teacher who spent most of her career at Rocky Mountain High School in Fort Collins, made a habit of taking all of her classes outdoors for authentic field experiences as much as she was able. “Kids would light up, and they were so passionate about learning when they were doing science outdoors,” Carol says.

River Watch

From 1996 through her retirement in 2016, Carol’s students participated in River Watch, a statewide volunteer water quality-monitoring program operated in partnership between River Science and Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW). This citizen-science program works with voluntary stewards to monitor water quality and other indicators of watershed health and utilizes this high-quality data to educate communities and inform decision-makers about the condition of Colorado’s waters. Carol had a team of River Watch students every year that went with her to two locations monthly to collect data, one site on the Poudre River in Fort Collins, and another along Spring Creek near the high school. She and the students created wonderful memories together by exploring outdoors.

“One time, the students wanted to do a full moon water sample,” Carol says. “I went along with it! Why not? We had a blast in the dark trying to follow all the protocols to collect the water while laughing and splashing under the full moon. We got back to Rocky at 10 pm, and still had to process all the samples. The kids talked about that for months. Through River Watch, I created vibrant relationships with dozens of students.”

“We had a collection day scheduled shortly after the big flood in 1997. When we got to Spring Creek, it was unrecognizable. The students were so excited to collect the water that we couldn’t resist. I kept them safe, but a city worker reprimanded us for being too close to the floodwaters. “I know those students will never forget the oily sheen on the water’s surface, the dramatic change in substrate, the missing gravity bridge.”

In 2011, the students collected invasive bullfrog tadpoles and brought them back to the classroom to raise. Carol infused lessons on this species into her biology class because of the curiosity of her River Watch kids. After the High Park fire in 2012, there was so much ash in the Poudre River that it really impacted their water quality data. Then, following the post-fire flood in 2013, there were no more bullfrogs in the river!

“Students were curious about things when they could study patterns and ask their own questions. The High Park fire created a lot of interesting questions. Comparing two water sources always produced questions! When students ask their own questions, they dig deeper into the subject and their curiosity inspires learning.”

Learning Outside

“When students read about something, they might learn something about it. However, putting your hands and feet in it, feeling it, and walking with it creates personal knowledge through experience and brings a passion to the learning that will never be forgotten.”

Carol explains that it is much easier to create bookwork lessons than it is to manage authentic science experiences whether they are in-class labs or outdoor field work. Additionally, there are so many barriers these days to getting kids outdoors that teachers often give up. Between composing a permission slip with all the legal requirements included, and then collecting them back from every student; the near impossibility of getting a bus at the times they are needed, and then finding the money to pay for them; figuring out a way to cover classes or students who are not attending the field trip; pushback from other teachers, parents, or administrators who don’t understand the value of the field trip, it’s a wonder we get kids outside at all anymore! Carol managed to do it consistently.

“Field work feeds the teacher’s soul!” Carol exclaims with excitement. “The payback is tremendous! Barriers fall away when I feel the students’ excitement during the trip, and hear kids talking on the bus saying things like, “Why don’t we do this more often?”

Finding Opportunities

Carol was always looking for new opportunities to learn herself, which led her to new opportunities for her students. During the Chronic Wasting Disease outbreak in Colorado mule deer, the Colorado Division of Wildlife offered a few teachers the opportunity to assist with field research, and Carol jumped at the chance. Feeling the blast of helicopter blades overhead as a mule deer in a net was lowered gently for inspection by a wildlife veterinarian was an adrenaline rush she won’t forget.

Later, her biology students got to participate in a wildlife research simulation on the CSU campus by taking fake blood samples from a mule deer model with a CSU graduate student teaching them the protocols. Because the field experience was so powerful, the students were excited to learn and apply statistics and radio telemetry through hands-on activities at CSU.

“Once people know you like to do extra things, they reach out to you,” Carol says. “I had a lot of people contacting me through the years asking if I wanted to join this or that research.”

Through a GK12 grant opportunity, Carol had 4 graduate researchers from CSU paired with her classes. She traveled to the Arctic for summer research through this connection, and her students were benefitting by having the researcher in the classroom. One of the grad students helped her develop field research protocols for studying plants, insects, and soil nitrogen which she implemented with her classes in a microhabitat study. One parent wrote a note, “My daughter won’t be going because she is afraid of spiders.” Carol managed to convince the parent and the student that she should attend, and through exposure and experience, the student’s fear of spiders was at least abated if not overcome.

“Knowing who students are and developing relationships with them was the most important aspect of my teaching,” Carol claims. “It was easier to develop those relationships when we had authentic experiences together.”

“I found new things to involve myself in, often paying my own way for new opportunities.” For example, Carol took herself to the University of Pittsburgh for three summers to learn how to be a phage hunter! Tuberculosis bacterium are becoming drug resistant, and bacteriophages are the next idea in countering this disease. She was able to train her students to look for and isolate new phages from Colorado soils, and her AP biology students sent several novel phages to contribute to the bioinformatic genomic database at the University of Pittsburgh.

Collaboration

“There is power and possibility in collaboration.” Carol has always been inspired by other teachers and her students. Her partnerships in her school and her community were what kept her ideas flowing. “I was able to endure as a teacher because I was sharing the challenges with other teachers. I never did any of this by myself!” Carol lists dozens of names of those who shared her challenges, her joys, and her students.

Community connections were important resources for Carol. In 1994, she took the Master Naturalist training through the City of Fort Collins. She became passionate about birds, and saw opportunities for more field work with her students. She was good at grant writing, and procured a classroom set of binoculars and bird books as well as bus money for field trips. Her biology classes learned bird identification, and during spring migration they would go out together and look for birds. Carol still participates in the Audubon Christmas Bird Count.

“I still have former students come up to me in the grocery store and tell me which birds they saw this week!”

Connecting her high school students with elementary schools was another collaboration she enjoyed. “When kids teach kids, the happiness is infectious!” Her anatomy/physiology students would teach a heart or lung dissection to elementary students every year. Elementary teachers would contact her with the news that the school PTO had already set aside the money for the hearts for the next year right after her students completed the lessons.

Another collaboration was when her high school students designed and built traps for mountain pine beetles. They brought the traps to a tree farm up Rist Canyon and worked with Stove Prairie Elementary students to set the traps and collect the beetles for a field study. Place-based learning is important to Carol. Figuring out what is happening in our own backyard helps us to act locally to solve important problems. Making science real usually involves looking and wondering close to home.

Continuing Learning Outdoors

One of Carol’s students, Cassia Rye, entered an essay contest. The prize involved the student and teacher getting to take SCUBA lessons and spending time at the underwater research station Aquarius in the Florida Keys. Carol had never considered diving, having a bit of a fear factor. However, when Cassie won, Carol could not back down! The tables were turned. The teacher became the student. They dove together in the Keys, and even met three NASA astronauts 60 feet below the ocean on the Aquarius. A new outdoor experience led to even more underwater exploring that continues to this day.

Just because Carol is retired from classroom teaching does not mean she is retired from teaching! Carol participated in Monarch Watch with her students for 20 years, with her students raising caterpillars in the classroom. Students could observe how hormones change caterpillars into butterflies just as they move humans through puberty. “Peoples’ appreciation grows as they wonder about things. Studying monarchs is an interesting way to gain that wonder and appreciation for our planet.” Now, Carol has 12 families in her neighborhood participating in Monarch Watch! Together, they plant milkweed and raise monarch caterpillars. She continues to spread the love of science and is helping to create life-long learners in her community.

How can you give your students authentic field experiences?

What opportunities have you found lately to expand your knowledge?

Who can you collaborate with?

“Life is eternally fascinating! Challenge yourself!”

-Carol Seemueller

NoCo Science Education Blog: Collecting Rain, Collecting Data, and Collecting Scientists with Nolan Doesken and Noah Newman

By Victoria Jordan

Station reports from the CoCoRaHS website:

“KY-LG-10 (12/13/2021)- Community trying to recover from Sunday morning tornado. Lots of damaged trees down, barns destroyed, houses damaged with roofs blown off, garage doors buckled, trees on cars, and houses, travel trailers and motor homes blown over. Probably excess of 100 fatalities – 10 known in joining county. A mile of 3 phase electric lines down-poles twisted and snapped.”

“Dear CoCoRaHS,

My home was destroyed in the recent tornado in Kentucky. My rain gauge vanished like Dorothy’s house. I will have to stop reporting my data for awhile.”

What IS CoCoRaHS?

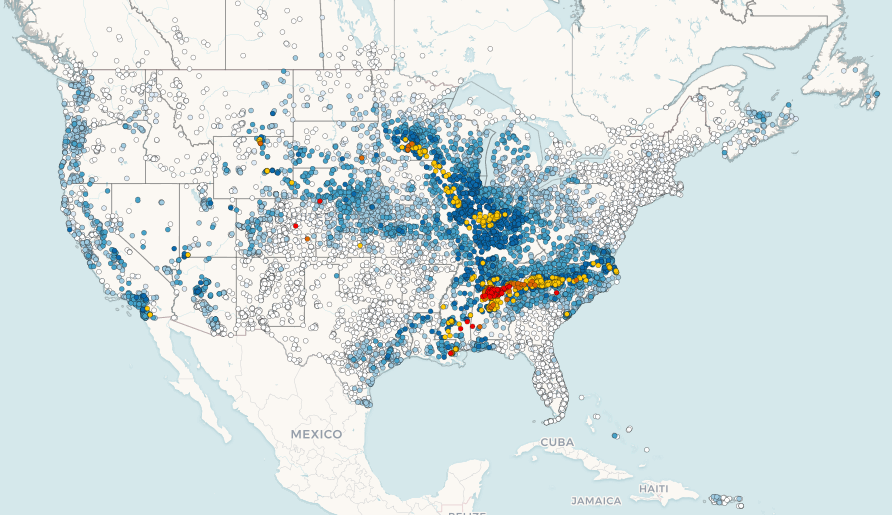

CoCoRaHS is the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow Network. It is a non-profit, community-based network of volunteers who measure and report rain, hail, and snow in their backyards. CoCoRaHS is the brainchild of Nolan Doesken, retired Colorado State Climatologist. You can read more about the history of CoCoRaHS, check out the data, maps, and educational materials here: https://cocorahs.org/

What CoCoRaHS really is goes beyond the network of over 25,000 volunteer reporters from every State, Canada, Puerto Rico, Bahamas and the Virgin Islands, and its hundreds of users of the data, including The National Weather Service, other meteorologists, hydrologists, emergency managers, city utilities (water supply, water conservation, storm water), insurance adjusters, USDA, engineers, mosquito control, ranchers and farmers, outdoor & recreation interests, teachers, students, and neighbors in the community. Yes, it is all that. But, what cannot be captured in the data is the teamwork, collaboration, and sense of community that brings people together in this seemingly simple citizen science program.

“Nothing I have ever done has resulted in so many friendly collaborations, all with just a simple backyard rain gauge!” says Nolan Doesken, the charismatic founder and backbone of the network. “Our youngest volunteers are 4-5 years old (with parental help), and our oldest is 103.” Nolan writes personal welcome letters to at least 20 applicants each month, and his newsletters contain both scientific information and personal notes about life on the farm that keep volunteers begging for more.

“Dear CoCoRaHS,

My husband recently passed on. For the past many years, he got up every morning at 6:45 so that he could check the rain gauge and report his data. You kept him going. Now, my children want to take the gauge and teach their children how to report data and maintain a connection with Grandpa. How can we transfer his account over to them?”

CoCoRaHS Creates Scientists

As volunteers enter their data, they have an opportunity to comment.

“AL-MG-17 (09/19/2021) – Rain continued throughout the night. The air is humid but cool this morning. Interestingly, we have 5 garden spider webs around the house. The most before was 2. They all appeared over just the last week or so.”

CO-LR-676 (03/15/21) – 1.62” moisture, snowpack depth 26”; The new snow amount is just an estimate because of drifting. It is likely more due to compacting. I had to go out a window to get to the rain gauge. Snow blocked the door.

“It amazes me how dedicated people are to the process,” says Noah Newman, education specialist with CoCoRaHS. One person wrote that CoCoRaHS is helping them stay sober with their AA commitment because they can’t get up to check the rain gauge at 7:00 am if they are hungover. When Nolan and Noah were trying to fill in some blank spots on the map by recruiting volunteers, one observer told them, “Come on over for dinner. I’ll put you in touch with our County Commissioner.”

One of the highlights for Nolan was when the White House installed a CoCoRaHS gauge in Michelle Obama’s White House garden, and staff members were reporting the new station data. The Washington Post used their data in their daily weather reports while the station was operated. Nolan was honored at the White House science fair reception that year, and was photo-bombed by Bill Nye!

Noah works with K-12 schools across Colorado and the nation to develop lesson plans that allow students to become scientists. “I have many star teachers that have students report data throughout the school year, and some kids end up starting a station at their house. One particular teacher works at a juvenile detention facility in Oregon. The kids are so proud to be able to report data and learn atmospheric science. One graduate used his CoCoRaHS certificate to help him land a job as a forest firefighter.”

Motivation

CoCoRaHS has one of the largest volunteer networks of any citizen science program. With a 60% retention rate, they rank among the top programs in the nation. Consistency with the staff over the decades has been a key component to the success of the program. In a recent study to determine what motivates volunteers to continue reporting, many people commented on the value Nolan brings to CoCoRaHS.

“I’m reporting data because I was asked to do it by Nolan.”

“My brother roped me in, and I just keep doing it because I’m reminded in the newsletters and blurbs on the site how important the data is.”

“I love Nolan and his newsletter!”

Noah adds that, “CoCoRaHS is a bit ‘gamified’ because each rain event is different, every day the map looks different, and it builds curiosity.” Reporting really took off during Covid because people were stuck at home. “We provided a way for people to be involved in their community in a positive manner, doing something that actually matters.”

What About the Data?

“Without CoCoRaHS, we would not have neighborhood-scale data,” Nolan says. Precipitation is so variable in the span of neighborhoods, that the goal is to have one rain gauge every square mile in urban and one every 36 square miles in rural areas across the nation. “One unique aspect of having this much coverage means that we can replace time with space to gather enough data to adjust historic averages,” Nolan adds. They have done statistical analyses in several parts of the country, and have found that if they have 10 or more volunteers reporting regularly in a 10 mile radius, they only need 2 years of precipitation data to equal the value of 100 years of data from a single “official” weather station. “It doesn’t line up quite right on the extreme ends of the data,” Nolan clarifies, “but, for things like the historic averages and 100 or 500 year weather events, it works great.”

When NASA was still launching space shuttles, they needed to find a way to figure out if hail was damaging the tiles on the shuttle while it was sitting on the launch pad. CoCoRaHS to the rescue! The hail pads that are used, simply heavy-duty aluminum foil covering a square of 1” Styrofoam, are able to record enough data in a hail event to allow scientists to determine whether the shuttle can fly. Insurance companies can use the data to determine car and roof damage, as well.

Quality Control of the data is a big concern, and a lot of manpower is put into ensuring that volunteer data is reasonable and accurate. Coordinators throughout the nation monitor State data, and continue to educate volunteers whenever they notice mistakes. “We have an endless supply of new people who make the same old mistakes,” Noah says. “Data entry has decimal point mistakes. Snow depth gets tricky with wind and drifts. People often read their gauge correctly but enter the wrong day or time.”

“We are in an interesting time, with everything going digital,” Nolan says. “Raindrop spacing, drop size, wind all make a difference to the catch. But, what we have found over the years is that our CoCoRaHS rain gauge provides the most accurate data of any type of precipitation measurement device.” He is hopeful that the new generation of scientists and volunteers will be committed to continuing to use the manual gauge. “Being out in the weather allows people to have a rich experience. Every drop counts.”

You can count, too. Visit the CoCoRaHS website https://cocorahs.org/ to purchase a gauge, apply for a station number, find lesson plans, attend an online or in person training, make a donation, and study the maps. Join the CoCoRaHS Juggernaut!

Listen to the original CoCoRaHS song by Dewey Longuski and lyrics by CoCoRaHS volunteer Ann Donoghue (CO-LR-36):

https://media.cocorahs.org/video/ComeHailOrHighWater.mp3